This amazing picture of a Eurasian Brown Bear was taken in a Slovenian forest, but I reckon you could find a similar looking landscape in the Peak District.

The question to ask is this: next time you’re out for a walk, how would you feel about encountering the scene above?

In Sunday morning’s edition, I covered some of the ideas behind the ‘Rewilding The Future’ exhibition, just opened by Sheffield Museums at Weston Park. In this piece, I’m looking in more detail at the wild beasts we might see out there before too long. Alistair McLean, Curator of Natural Science at Sheffield Museums Trust, says his aim in the exhibition is for us to ask questions.

Brown Bears used to roam around the UK, but were hunted and killed out of local existence, retreating into the deep forests of Russia and cental Europe. So in some ways, assisting those big beasts to return home is righting a wrong. You could say that reintroducing the animals is “undoing an act of persecution,” Alistair explains.

Bears, lynx, bison, eagles, beavers and many more creatures that once lived here are being considered for a return, with varying degrees of likelihood.

But first, a button asking you to subscribe so you can read more of this kind of thing, and then an introduction to what rewilding might actually mean..

Rewild to When?

Sheffield and the Peak District around 350 million years ago was a swampy sea. Hence the fossils of sea creatures in the limestones of the White Peak. And then for millions more years, huge plants like tree ferns spread across the swamp, which as they died and decomposed laid down our coal seams.

Living among the tree ferns were huge insects and amphibians, two feet wide dragonflies, monster millipedes, and big green things Alistair McLean describes as like “really big frogs.”

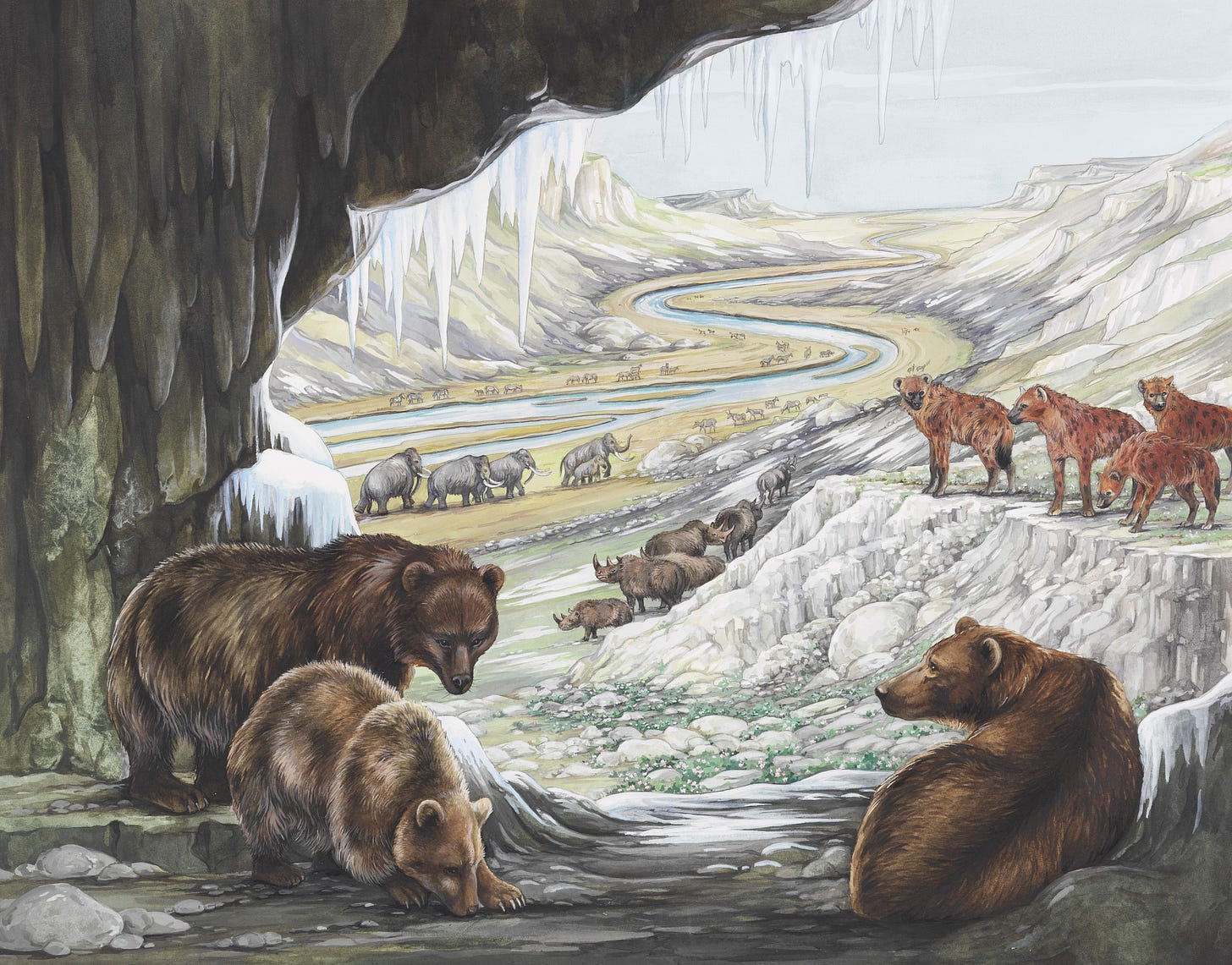

The impossibilty of rewilding to the times of frogs as big as people and drone-sized dragonflies leads to the local rewilding question: just when in Sheffield’s natural history should we turn our focus? The answer, now broadly agreed among ecology professionals, is the wildlife that has lived here since the end of the last ice age 10,000 years ago.

So no elephants or hippos, no lions, or two metre millipedes, but there are still plenty of pretty interesting beasts we might welcome home again. A selection from the list Alistair wants us to consider is below, along with my entirely subjective assessment of if and when we might see them here again. (Although some are already arriving without our help).

White Tailed Eagle

Otherwise known as Sea Eagles, these are big birds, with a wingspan of over 2 metres. They were hunted to extinction in the UK as they eat small mammals, lambs, and game birds as well as their favourite fish. But succesful reintroductions in Scotland and the Isle of Wight have led to birds spreading out to new territiories elsewhere.

Earlier thoughts of eagle reintroductions led to disquiet among ornithologists, because eagles are not fussy about whether the other birds they eat are bred for shooting, or on a rarity list. Here’s a quote attributed to a local naturalist in the 1930s:

“Expecting a landowner to put up with an eagle is akin to expecting the owner of a china shop to put up with a bull.”

Neverthless, a young female White Tailed Eagle has appeared in the Peak District in recent summers, looking for food here before returning home to the south coast over winter. It’s not yet breeding here, but it’s probably only a matter of time.

Local Rewilded Status = kind of here already.

Bison

The Steppe Bison, which used to live here, is no more, but its descendant is the Wisent or European Bison, living now in eastern Europe. Large herbivores root around and mix up the soil, carrying seeds and spreading vegetation around. This is why conservationists like to see highland cattle on the moors, effectively because they (like bison) help reduce monocultures like heather and allow other plants to gain a foothold.

Our original native cattle (the Aurochs of European legend) are also extinct, but the Wisent is actually descended from the Aurochs as well as the Steppe Bison, and there’s now a trial herd in Kent, where they root around in an enclosed forest so ecologists can see how they get on. And they had a baby bison recently.

Local Rewilded Status = entirely possible.

Grey Wolf

One of the apex predators we’re missing. Wolves would help keep deer numbers down, and are very unlikely to attack humans, said a ranger from Germany I met a few years ago, who has ‘wolf education in schools’ in his job description, because wolf packs are now spreading around his country.

“You just sing or make some noise when you’re in wolf territory, and they stay out of your way,” he explained. Wolves are intelligent creatures, and have no desire to mix with humans, he said. But they are admittedly a hard sell in a densely populated country like England.

Local Rewilded Status = subject of debate.

Eurasian Beaver

A ‘keystone species’, which means having them around creates or preserves habitats for biodiversity to grow. Many ecologists think beavers would be ideal for places in the Peak District and around Sheffield where we’re trying to recreate wetland and keep rainwater in moors and woodlands. A feasibility study has been done, I gather, but decisions have not yet been made.

Meanwhile, existing populations are spreading from Scotland and south west England on their own.

Local Rewilded Status = on their way.

Brown Bear

Just like wolves, bears will occasionally eat deer, and just as importantly, keep them nervous and on the move, and so less likely to stick around long enough to devour young woodlands.

At present, the growing deer population around the city have no natural predators, so they often stop to eat an attactive woodland until most of the young trees are gone. This is why new woodlands at Houndkirk and Whirlow, for example, are now covered in ugly tree guards for years.

Bears also eat lots of berries and seeds as they travel, and thus spread those seeds into different places and different habitats, increasing biodiversity.

A very small number of bears as apex predators at the top of the food chain offer a huge and very simple boon to biodiversity. They alter things in a good way (even their droppings benefit the soil, it’s said, and as we know, bears do defecate quite a lot in the woods). And if and when prey animal populations die down, bears adapt in a few years by producing fewer baby bears.

Bears would prefer to stay away from people, but they’re very big, and if cornered or surprised, there may be an ‘interraction’ as Alistair gently puts it. In America and Europe, there is always a very small chance of an attack by a bear.

Weighing that up against how returning the Peak District to a more natural state will also benefit humans, is an almost impossible question to answer. But we should ask it, says Alistair, which is the purpose of the exhibition.

“The question I ask myself is whether I’d be happy going for a walk in the Peak District knowing I could encounter a Brown Bear. It would certainly change how I’d go for a walk in the Peak District.”

Local Rewilded Status = subject of debate.

Pine Marten

Pine Martens used to live here until fairly recently. Alistair has a stuffed version, now faded from its natural chocolate brown by sunlight at exhibitions where it’s featured since being presented to the museum in 1926. (It had been killed in a snare on the Broomhead estate, he explains, which says all you need to know about why the species disappeared locally).

Pine Martens are fairly vicious killers which, in their current main homes in Scotland and Wales, have predated and frightened any existing American Grey Squirrels until their numbers go down. Unlike small and nimble Red Squirrels which know how to get away to the thinner branches, larger Grey Squirrels evolved to avoid the likes of American Bobcats, and have no idea what to do if a hungry Pine Marten appears.

In general, because Grey Squirrels can carry disease to native Red Squirrels, and outcompete them for food, if greys go down, reds go up if the latter can find their way into a wood they once inhabited. So Pine Martens are associated with resurgences of native Red Squirrels.

And the native Pine Marten populations are spreading. A scientist announced recently that Pine Marten DNA had been found in a Peak District river, and there have also been possible local sightings. Good news, surely?

Well, have a look at the beige former Pine Marten in the museum. It’s quite big, so you might wonder what you’d think about one of those biting into dazed American squirrels in the trees above you.

Local Rewilded Status = probably already here.

There are also Eurasian Lynx (shy but quite big cats, with few arguments against their reintroduction, except from some landowners, but they’re not here yet), Eagle Owls (occasional visitor that’s almost as big as an eagle, but wider) and Wild Boar (good for woodlands, but big and scary, and already spreading in the UK, so possibly arriving here soon).

Alistair points out that rewilding is not just about big beasts, it’s as much about cleaning up our rivers enough for Otters to return, putting up nest boxes for Peregrine Falcons or Pied Flycatchers, or allowing native plants and grasses to thrive in parks and woodland.

But there’s nothing like big scary animals to focus attention on a debate, which is just what he wants to see. (Do join in by posting your thoughts in the comments below.)

So, I ask him, which of these animals, these bears, and wolves, and beavers and eagles would you like to see around here? He pauses, and stresses this is his personal opinion only.

“They have a right to exist where they should and need to exist,” he says. “I’d like to see all of them.”

Finally, we’re back on Sunday with a new post, news, and a few selected events for the following week. (And here’s a few things on this Saturday as a preview). Please, if you have events coming up - let me know in the comments below).

Sat 27th - Drainspotting - Sheffield's Victorian Pavement Features Walk from Rustlings Road

Sat 27th - Morning Moth Trapping session at Wardsend Cemetery - 6 am

Sat 27th - The Great Sheffield Flood Tour walk at Wardsend Cemetery - 2pm (£2 donation)

Thanks for reading. Please add your comments on these subjects below. Do you want to see bears in the woods and wolves on the hills? Do let us know.

If you’ve been before, please subscribe, and if you like what you read, becoming a full paid subscriber for £4 a month (less for a year’s subscription) will be another step towards making this local publication sustainable. Thankyou.

This is really positive and I would be very much pro all of these being reintroduced except with some reservations about bears... As someone with a young family, I would be apprehensive about going for a walk and encountering a bear, and would be sad to have to avoid certain areas of our beloved Peaks.

I also would like to see all of these animals reintroduced, simply because they have a right to be here just as much as we do! The anonymous commenter has a good point though about how wolves and bears may further discourage people from visiting. I admit the thought of encountering a bear makes me particularly nervous!

I’m an American living here in Sheffield and have visited several American national parks and wild spaces where you might encounter bears, mountain lions, etc. There are lots of rules in place and measures taken to ensure safety, and generally the animals tend to keep to themselves. There is a big difference though in the national parks of the US and the UK... obviously the US is so large that there is a lot of space for full on wilderness. There aren’t towns, villages, and people living in the parks (except for rangers) like there are here in the UK. It’s definitely tricky to determine how we can rewild while also keeping people safe.