There are still some Peak District visitors who think moorland should naturally look brown, or purple for a couple of months in summer. But heather monoculture moorland is not at all natural: it’s usually been made that way by generations of owners who like to breed and shoot red grouse - and farming grouse ready for slaughter in August means providing lots of young heather shoots, which growing grouse like to eat.

Campaigner and writer Bob Berzins has explored our local moors for years, and often finds a damaged and desolate landscape, the result, he argues, of a type of grouse moor management that’s bad for biodiversity and climate change, and bad for us.

He’s written this post to outline his view that we should stop paying millions of pounds to grouse moor owners, and bring our moors back to us. We’d love to hear your comments below.

Many of us find grouse shooting disagreeable, but should we just see it as an activity involving a few participants that the rest of can simply ignore?

Unfortunately not. Grouse shooting over the last two hundred years has changed the ecology of huge swathes of England’s Pennine uplands, and that change has a negative effect on millions – those living downwind and downstream, and the global community affected by carbon emissions.

In a biodiversity and nature emergency, these uplands are robbed of life, with the most glaring example being the continued wholesale persecution of birds of prey.

The land itself has been degraded, while the ownership of that land has often remained in the same family. Right now we pay many of those landowning families millions of pounds in subsidies, and millions more in restoration grants, in an attempt to put right the damage already done. But that damage continues.

There has to be a better way. I wrote a personal blog on these issues for Raptor Persecution UK, and in this post for It’s Looking A Bit Black Over Bill’s Mother’s, I hope to draw attention to this disgraceful use of public money, and make the case for compulsory purchase of land that’s being managed to the detriment of local communities.

The English Devolution Bill is due to be debated in Westminster parliament this autumn. The proposals in the bill will empower local communities with a strong new right to buy for valued community assets.

The examples given in the bill are mainly urban, but Labour movement and land activists, and many others, have been calling for sweeping changes to land ownership.

Sheffield Labour Councillor Minesh Parekh made the call to Nationalise the Bogs in The Tribune magazine when he was part of Olivia Blake’s team in a shadow Defra role. Land For the Many (2019) produced for the Labour party proposes a structure to enable community ownership using the example of the moors above Hebden Bridge where: “The community could reasonably argue that such land serves a more important public purpose as a natural flood defence than as a grouse shoot”.

Eminent campaigners such as Mark Avery and Guy Shrubsole argue for public ownership of uplands. An example of how this might work in practice is the community fundraising and management of Tarras Valley in the Scottish borders which has shown how to bring life to a depleted grouse moor. So it can be done.

Why Is The State of Our Moors Important To Sheffield?

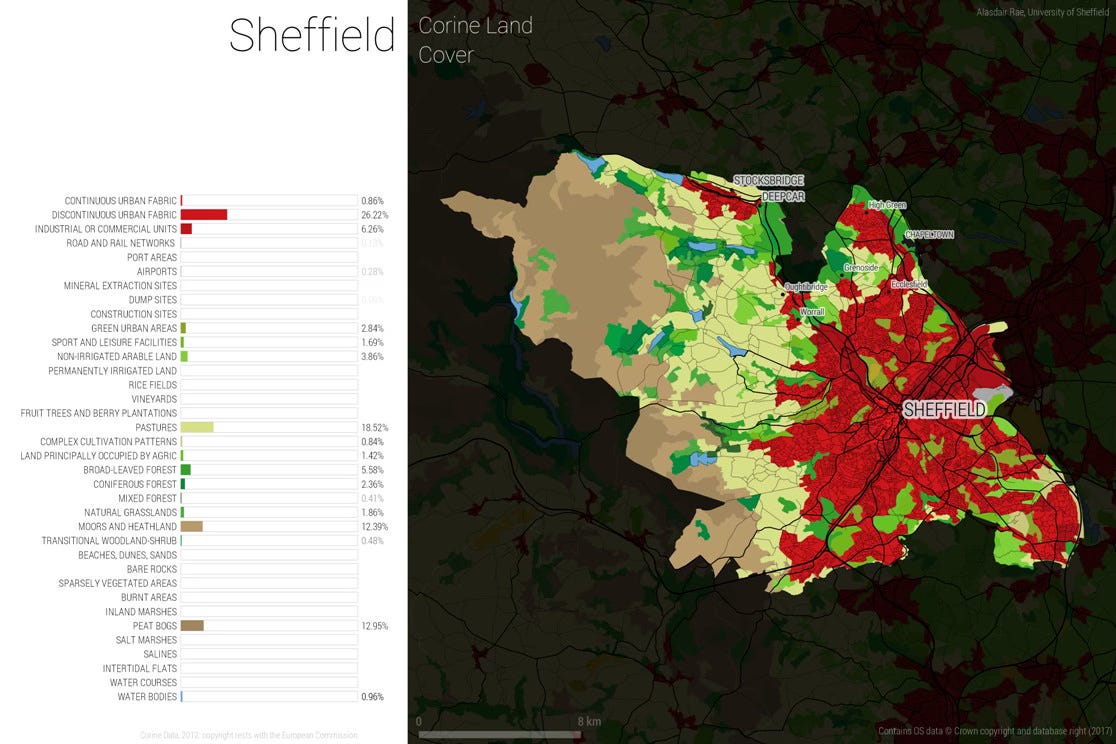

I show this land use map in every talk I give to illustrate how a quarter of our city is moorland, and everything that happens on those moors affects our lives.

These moors could provide huge benefits, locally and globally, but instead many of them are failing, by the Government’s own measure.

We deserve better. To add to that sense of injustice, ownership of these uplands all over the country was wrenched away from the community in the past, usually to become the sole property of one person: The Lord of the Manor.

The Enclosure Acts 1790 – 1830

In the early 1800s, MPs were usually rich, aristocratic landowners, and unsurprisingly they voted through a series of individual Acts of Parliament where moors, waste land and commons were shared out between themselves.

In Sheffield, you’ve probably noticed Norfolk, Fitzwilliam and Rutland as the names of streets, parks and pubs, and it was these aristocrats who received the majority of local land. Earl Fitzwilliam ended up with Bradfield moors, and this family are still the owners today.

The land marked in this 1898 map includes the Fitzwilliam Wentworth Estate to the east, along with Howden Moors owned by the Duke of Devonshire (which is now part of the National Trust High Peak Estate). In my view, this ‘preservation’ by the Game Association has left a legacy of dry, denuded moorland in unfavourable condition.

It took at least six individual enclosure acts for the Duke of Rutland to get hold of the Sheffield Eastern moors, and a hundred years later we have death duties to thank for the sale of this estate eventually to the National Trust, Sheffield Council and the National Park Authority. This land is now managed for the benefit of us all by the Eastern Moors Partnership.

But it seems the Rutlands couldn’t bear to be without a grouse moor, and they bought Moscar Estate from the local snuff-making Wilson family in 2016. (The Wilsons acquired the land from the Duke of Norfolk in 1897).

The other large landowning estate overlooking Sheffield is Broomhead, where a different Wilson family have been in residence since the 1300s, again benefitting from enclosure to get their hands on the moors.

The Dukes of Norfolk, Rutland and Earl Fitzwilliam were and remain some of the richest and most powerful landowners in the country. (Source: David Hey - A History of the Peak District Moors).

It’s worth noting that whilst the Fitzwilliams were enjoying their grouse shooting on the moors, 36 miners died working in their Elsecar collieries between 1868 and 1895. The Fitzwilliams owned not just the collieries but the surrounding land and miners cottages – so they pretty much owned the workers themselves.

Who Takes Ownership?

I’ve kept an eye on the moors above Sheffield for many years, not just when running or walking on the moors themselves. Anyone can access the DEFRA ‘MAGIC’ maps (meaning Multi-Agency Geographic Information for the Countryside), and with a bit of effort I’ve also unearthed a wealth of information about grants to landowners from Freedom of Information requests.

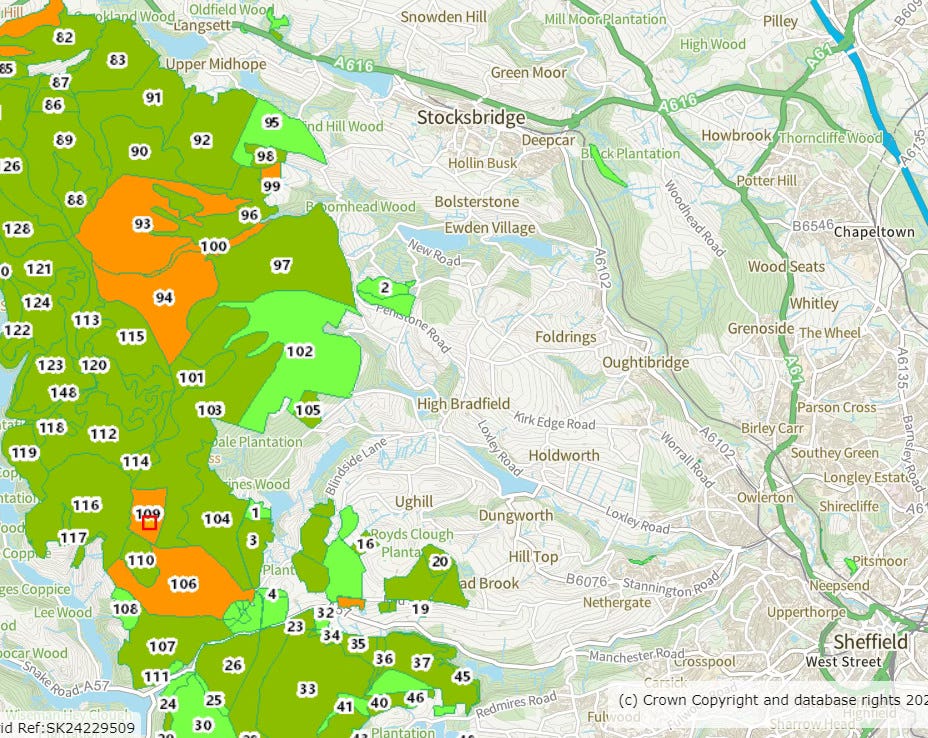

The land on this map shows Sites of Special Scientific Interest, land with the highest conservation designations meaning it’s the most precious we have in the UK. The map is a bit misleading: you’d think green would mean good condition, but the Government’s conservation body Natural England assessed the majority of these units as ‘unfavourable but recovering’ back in 2011, before the Cameron/Osborne regime slashed the Natural England budget.

Note: The official assessment of SSSIs ranges from the highest categories of ‘favourable’ and ‘unfavourable recovering’ (meaning either the land is adequately conserved or measures are in place to get it to that stage) to ‘unfavourable no change’ and ‘unfavourable declining’ (meaning no measures are in place to get the land back to favourable condition, or it’s already declined and is heading for the self explanatory ‘part destroyed’ or ‘destroyed’ categories).

These units of land were given ‘recovering’ status because of new stewardship agreements which were supposedly going to transform the land, but as yet this hasn’t happened. In my view, these moors are failing.

If we look at the units in pale red (which have been surveyed more recently) Middle Moss (94) is on the Broomhead estate, which I learned received £530,922 in 2016/17 in capital grants for restoration of this unit and others, as well as around £2 million over a ten year period in Stewardship funding, mainly to improve conservation.

Surely such expensive restoration work on Middle Moss would result in a huge improvement? And we’d now be seeing the benefits?

It seems not. The assessment on this land is ‘unfavourable’ - no change. The land has been in the same family for 200 years – two centuries of burning and drainage, to dry out the landscape and promote a monoculture of heather, for the benefit of grouse breeding and shooting. That can’t be undone with a half million pound tranche of restoration money. It looks like it’s left to the taxpayer to provide a bottomless pit of money to repair this damage.

The atrocious state of grouse moors is not limited to the Peak District. The Duke of Devonshire’s family have owned Bolton Abbey Estate since 1748. Located in the Yorkshire Dales National Park it’s been largely assessed as ‘unfavourable declining’ condition (bright red) in the screen grab below:

The Barden Moor unit assessment in 2024 states “activities relating to grouse management are impacting throughout”. And on Thorpe Fell “Blanket bog in this unit appears relatively dry and there is a notable lack of sphagnum cover / species...... Rewetting, re-vegetating exposed peat and reduction in the intensity of / location of grouse management activities would all likely see an improvement in the condition of both dry heath and blanket bog in this unit.”

Managed to death, I’d say this huge area of moorland is failing under its current owners.

A Constant Brake On Improvement

Back in the Peak District, Moscar Estate also received huge sums for restoration - £348,800 in 2016/17, but Black Hole Moor (unit 109) was assessed as ‘unfavourable no change’ in 2022, with previous burning noted as one of the contributing factors.

We all suffer as a result, because that ‘unfavourable’ assessment means rainfall onto the moors is flooding downstream, and carbon is flooding into the atmosphere. Grouse moor managers know that dry, heather-dominated moors have provided ideal conditions to rear a huge number of grouse over the last 200 years, and I don’t think they’re going to give that up.

Natural Flood Management

Sheffield suffered catastrophic flooding in June 2007. The Sheffield moors are the highest part of the catchment – the area with highest rainfall.

Seventeen years on there’s been some progress to reduce that flood risk, but nowhere near enough. The Environment Agency and partners are starting to look at natural flood prevention measures. But crucially nobody has yet come up with a coherent overall plan of how to manage all moorland to provide the best mitigation against flooding.

If blanket bog (the high areas of deep peat soils) is still in unfavourable condition, that means gully blocking (using stones or other dams to hold water on the moors) has not transformed the landscape. The dams need to create mounds of sphagnum and a wider habitat where the water table is at the surface all year round. And there’s still 50% of moorland on thinner peat soils – known as Dry Heath.

I'd say burning like this is the worst possible management to prevent flooding, but it's usually described as essential by moorland owners . Under current arrangements there’s zero chance of seeing trees, scrub, more varied vegetation and measures to retain and increase peat coverage such as we’re seeing on blanket bog.

Burning on deep peat (more than 40cm) was supposedly prohibited by the government’s Heather and Grass Burning Regulations from October 2021. We’ve had a token prosecution at Midhope which did nothing to prevent the burning on Fitzwilliam Estate over the last three seasons, burning that many campaigners allege is illegal. Another example of grouse moor managers desperately trying to maintain dry, heather dominated moors, and apparently another example of our authorities looking the other way.

Time To Take Back Our Land

Two hundred years of grouse moor management is a major factor in the dire state of our uplands, yet the taxpayer continues to fund practices which I believe cause real harm to local and wider communities.

We are paying for this land over and over, through subsidies and grants to repair damage already done, yet these crucial habitats remain the property of a handful of individuals.

This is land which was wrenched away from the community generations ago, and it needs to be taken back to provide benefits for us all. Extending the community right to buy to our moorlands is a start. But we need more – a programme of moorlands coming under state ownership through compulsory purchase, if necessary.

Please start by lobbying your MP over the English Devolution Bill. And if you want to hear more about all this, Guy Shrubsole is doing a speaking tour with his new book.

We’re getting closer every week to our 250 paid up subscriber target, which will enable us to run more posts like this, and lots more. It costs just £4 a month to join the 230+ full, paid up wonderful members who are already part of our unique social media magazine.

Take a free trial, or upgrade to paid below.

Thanks for making past archive articles accessible, it is so good to be reminded of Bob’s article and the true reasons behind this staggeringly damaging moorland ‘management’ (aka burning) Just in the last month (March/April 2025) we have seen horrendous damage caused by dozens (hundreds?) of wildfires all across the UK - and news reporting and the usual keyboard warriors on social media just call for the hanging of errant youth and urban picnickers/bbqers with very few mentions of the landowners as being responsible for these ‘controlled’ vegetation burns being mismanaged and going out of control. We all know the recent huge fire on Beeley Moor, as well as one we witnessed in the Berwyn mountains recently in North Wales, were lit by the landowning establishment whose interest in this land is to benefit them from huge fees for grouse-shoots later in the year. Crazy that they are allowed (licensed!) to burn our precious peat Moorland in this way for their own profit. Destroying peatland, releasing carbon and drying out the land (in an already very dry Spring!) is just madness! Not to mention the earlier ground nesting bird season that we see now due to climate change - the damage to the wildlife of our moorlands from these fires is heartbreaking. This article has reminded me to look up progress on the Devolution Bill and any impact on land ownership and management - keep up the good work Bob - how can we help!?

Is there a good resource to learn more about the Devolution bill? Is it known when it will be debated? I'm trying to organise a letter writing event for my local climate group

Thank you!