Amphibian Alert, Helen Mort on Ethel Haythornthwaite: Sun 17th March 2024

Are frogs (and toads) about to croak? And Sheffield poet Helen Mort on the city's trailblazing countryside access pioneer, Ethel Haythornthwaite.

Morning. We’re looking at frogs, toads and newts today, partly because they’ve been very busy over the last few weeks trying to create lots more frogs, toads and newts, and partly because ecologists fear for their future. And thanks to Sheffield poet Helen Mort and CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire, we have an extract from Helen’s forthcoming book on countryside access and protection pioneer, Ethel Haythornthwaite.

Also, an apology: I’ve been a bit busy at all hours of day and night recently (see my latest Sheffield Tribune post for a kind of explanation), so have not caught up with our full members editions as well as I’d like, and one or two trial paid members have not continued their subscriptions as a result, which I completely understand.

Thanks so much to all of you who’ve been patient, though, and from next week I’ll be making some changes so there’ll be more for both paid and trial members.

Green Gallop

A quick note about the wonderful Grindleford Gallop trail race yesterday, mainly to publicly lay claim to finally running it (after the ice crisis last year), and to praise all the team at the 21 miles and a bit fundraiser for Grindleford Primary School.

The views are fantastic, but galloping round (actually stumbling and trudging in my case) I found myself thinking about the different landscapes in the Peak District, and the White Peak in particular.

To my mind, the wet wild woodlands on the route are amazing and full of life, even though the paths through them usually go horribly up or terrifyingly down. But there were also so many bare, boggy green fields, dotted with sheep hooves, but devoid of almost any other life. Controversial maybe, but vast green lawns are not my kind of landscape, even with Chatsworth House behind them.

Frog Watching

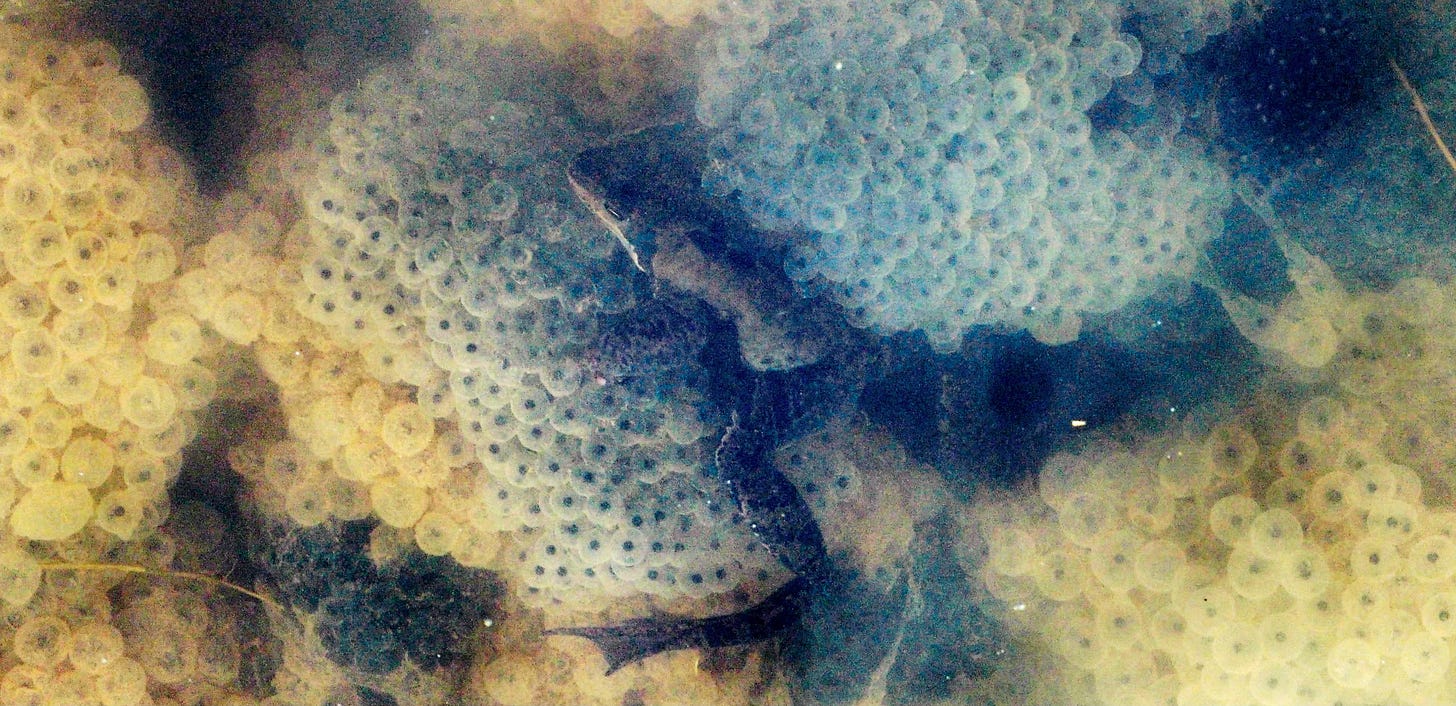

Frogspawn is more interesting than you think. Varying colours mean the spawn was laid at different times, says city council ecologist Angus Hunter, whose huge garden pond has clumps that are yellowish, some greenish or even blueish.

If you look carefully, he says, you can even see the white rather than black specks in the floating spawn of unlucky females which, despite the frenzy of male frogs in his pond, didn’t quite manage to get fertilised.

Frogs are worth clocking more carefully too: if you stay still around the edges of the pond, males of various greens and browns and even reddish colouring pop up to wait for any large female that happens by. This is evolution in action, says Angus.

Different coloured frogs are more likely to survive in different ponds if they’re camouflaged appropriately for that pond. Angus’s pond is new, though, so the local multicoloured frogs have yet to discover the fittest colour to survive in its waters.

Frog breeding season begins when the nights start getting a bit warmer. After spending winter hiding in the mud or a hibernaculum among sticks and stones, males venture out first to get their strength up by eating pretty much anything they can fit in their mouth, says Angus, and start croaking amorously to attract nearby females.

When the females arrive, often full of eggs, the males jump onto them ready to fertilise the eggs as soon as they’re laid. Angus shows me the special thumb of male frogs, to help them hold onto a female to be first in line when the spawn arrives.

Around the city, schools, teachers, and nature watching families like to witness all of this drama, often by scooping up some frogspawn and bringing it home to watch the tadpoles and young frogs hatch out and grow. But nowadays, if we want frogs (and toads) to survive, we have to think carefully about our springtime frog watching.

“We can all see them breeding now, but our amphibians are under more pressure than they have ever been,” Angus says. Two fungal diseases (Chytrid and Ranavirus) are afflicting amphibians in the UK, both probably brought into the country through the pet trade, he says. They spread very easily, and a few years ago Chytrid wiped out a whole colony of toads at Wire Mill Dam in the Porter Valley.

It’s likely that well meaning amphibian watchers spread the disease by moving some infected toad spawn (stringier than frogspawn) that they’d found in a puddle, or returned some diseased tadpoles there that were born elsewhere.

At present, the best advice is not to move spawn or tadpoles, but to watch the wildlife where it is. If you want your new wildlife pond to fill with amphibians, they’ll do it themselves, says Angus. Although most frogs stay near their home pond, around 25% of baby frogs seem to have an urge to travel, and will be looking for new ponds to colonise up to 250 yards away.

He adds that the welfare of the amphibians of this world is closely linked to other wildlife, since they’re usually so productive. Spawn and tadpoles are food for birds, fish and even tiny newts hunt for small tadpoles once they’ve hatched. So fewer frogs will affect a host of other species too.

Chytrid and Ranavirus can also be spread through plants, so make sure any new plants you add to your pond come from a source that can tell you their biosecurity record, he says. And if you do find a dead frog, toad or newt, contact the Garden Wildlife Health project, who are trying to monitor the spread of amphibian disease around the UK.

“These diseases are like Covid for frogs, but more lethal,” says Angus.

I’ll have a more detailed post on wildlife pond advice for full members soon, but in the meantime, if we want frogs (and toads) in our future, it’s best to leave them where they are.

Ethel

This year is the centenary of the charity CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire, and I’ll be talking to CPREPDSY in future posts. (Sorry for the impenetrable acronym, I have to watch my word count).

Many of the year’s events celebrate their remarkable founder, Ethel Haythornthwaite, who began their work to protect the local countryside,

Today, we have an extract from ‘Ethel’, a new book commissioned by CPREPDSY written by fabulous local poet Helen Mort, with her own take on Ethel’s work and letters. (I’ll have a longer extract from the book in a post for full members next week.)

“When I learned about Ethel Haythornthwaite's remarkable life and environmental legacy, I was shocked that I hadn't known about her before,” said Helen Mort by email. “I wanted to write this book to make more people aware how much they might owe to Ethel's trailblazing and campaigning.”

This chapter starts with an extract from Ethel Haythornthwaite’s long poem, The Pride of the Peak, which is included in the book. (Couchant is a heraldic term for an animal lying down but alert, legs and head facing forward).

Extract below supplied by CPREPDSY / Helen Mort and is copyrighted as such.

The Belt

Boldly the boulders o’er the valley stand,

And lift their heads against the lofty air;

Their jutting crags command the lower land

Like couchant dragons looking from their lair.

(The Pride of the Peak)

Where does Sheffield as I know it end? The notion of a green belt feels almost enchanted, like one of those children’s books where a tree reveals a hidden door, or a wardrobe is porous, or a knife cuts a gleeful window in the air. To find the edges of the city as Ethel would have experienced them, I have to go above it and below. In her essay collection Findings, Kathleen Jamie chastises us for not looking upwards enough, not studying the tops of buildings and cities. She describes a transformative moment in Edinburgh:

I was crossing Charlotte Square ... I happened to look up and, between chimney stacks and cupolas, saw this beautiful brass comet, a shining ball towing a deeply forked tail. Maybe I don’t look upward enough ... before the comet, I’d never wondered what the city raises ... what its domes and spires offer to the winds.

The same can be true of walking. We stare at the ground and miss the heights of things, the tips of trees, the uppermost branches. I am setting out uphill, cycling through Crookes and Crosspool, thinking of John Donne:

Licence my roving hands, and let them go,

Before, behind, between, above, below

I’m imagining those sensual words, addressed to a lover, transformed into an instruction to the feet, the body in landscape. License my roving steps I need to be above this stretch of open land, in front of it and overshadowed by it, pressed by its edges.

Today, I want to climb. I also want to dart under the surface of the city, to be a stitch, just for a moment. So I go to Redmires, where I can do both. I cycle to the place where the road runs out and abandon my bike, trusting that nobody here will steal it. If I can’t have faith in that, what can I have faith in? It’s an off grey day anyway, and there’s nobody to rob me except grouse (heard but not seen) and perhaps, I fancy, a curlew. I imagine a curlew atop a bicycle, stately, using its curved beak for balance. I strike off from the track to the left and answer the call of water, the path winding round to a little shore. I once swam here when the light was breaking, 5 a.m., chill and misty. Everything was under a sheet until suddenly it wasn’t: some unseen hand whisked the mist away and I was left with glassy water and the intent stare of the sun.

I am shedding layers. I am wading in. The mud sucks at your toes here, feels almost inviting, cushioned. There are ducks bumbling around by the bank, reprimanding each other, diving theatrically. I walk out until I am up to my knees, then my waist. I stop and watch the ripples that arch out from me, seeking. What do I want from this body of water? What does it want from me? Perhaps it wants me to leave it alone. Sheffield is full of ‘wild’ swimmers, cheerful on Sundays with their dryrobes and cameras. I imagine the ripples telling me to go home, go home, go home. But I am obstinate and – by my human nature – arrogant, so I trust myself to the water anyway and plunge in, up to my neck, then duck my head under and come up spluttering.

Later I will dry off and follow the path along to Stanage Pole and from there to the edge where I can peer down like a child who wants to be so much taller. Bracken. The spectre of the dark woods. The boulders that preoccupy climbers, fascinated by their small puzzles which feel like big puzzles.

‘I am always obsessed by one place or another,’ says M. John Harrison in his delightfully slippery anti-memoir. Wish I Was Here. Trying to describe a specific part of Wales (‘the enchanted hinterland’ between the A496 road and the Rhinogydd) he says:

There’s a real sense, in this landscape, of haunting, but rarely by anything specific. Yes the trace of use, but the moment you try to imagine by whom, or for what, or begin to believe you might ‘bring it to life’, it slips quietly back into the twilight downslope, the wind contorted tree. Every site is very calm, despite the things it must have seen. Even to say that is to say too much ... Where every thing you can say is either an understatement or an overstatement, a liberalisation or a fiction, it’s not your place to say anything.

I stand on the edge. I try to keep my mouth shut for once. I try to keep my mind quiet, but it is full of surroundings, Sheffield’s borders.

Describing her early apprehension of Sheffield, Ethel once said:

My childhood impressions of the city were – a gloomy noisy shape less phenomenon: but outside the city – there one began to live. To escape into the clean air, the gradual return to nature; with these came satisfaction and peace ... Along with this came the sickening realisation, as the ugly suburbs straggled out and the farms disappeared, that it was all going. But a helpless uneasiness may be replaced by action, and now some who comprehended the significance of Sheffield’s surroundings to her citizens, spend a large part of their lives trying to save them.

I’m interested by Ethel’s depiction here of Sheffield as female. The somewhat cloying image of landscape as the female body, to be protected but also conquered, or at the very least charted. The attempt to secure a green belt for Sheffield – a big preoccupation for CPRE over decades – could be seen as an attempt to enforce shape, to cinch the city’s waist; so much of the language from the time feels problematic to a modern audience, but the intent was to preserve and protect, to safeguard, to cherish.

Selected What’s On Out There (from Sun 17th March)

This is a small sample for this week taken from our full regularly updated listings service currently available in Round at Bill’s Mother’s. If you’re in a group who put on outdoor events and want me to include them, please stick them in the comments below as follows: Date, What it is, Online link.

Sun 17th - Sheffield Mass Cycle Ride, from Tudor Square

Mon 18th - Volunteer Session at Whirlow Brook Park

Weds 20th - South Yorks Orienteers public event - Redmires (£6)

Thurs 21st - Finding Lost Norton Park at Graves Park - Early Spring Flowers Walk from Charles Ashmore Road

Fri 22nd - Sheffield Cycle Tours from Sheffield station (woodlands)

Fri 22nd - SRWT Volunteer Work Day - Greno Woods

Sat 23rd - Parkhill Uprise cobbled cycling challenges

One of my new writing times is 4 am, as explained below. So sorry for possibly even more typos than usual.

Thanks for reading - and remember: F.F.S! Forward to Friends and Subscribe!

(And by subscribe, I mean free is fine as a try out for a few weeks, but after that a meagre subscription of £4 [or less] per month would be a real help to pay the bills.)

:

As a Tribble (well, Mill readers get called Millers!) I have read your reason for being a little late with your post. 100% sympathy to you - you’re a wonderful person, and any child would be lucky to have you as a dad, even if temporarily.

Those Chatsworth desert fields were a very strange place to be, I agree. Lots of pasture in Loxley where I live, but it's mostly for cattle, so it's walled and stiled and interspersed with odd bits of stream and lane. Much more human in scale, which is maybe not the right thing to be thinking about "nature".